There is a generation of Sudanese girls who never got to grow up; forced only to survive. Their girlhoods have been stolen by continuous turmoil: resistance, pandemic, and war. Each new beginning came with another ending. What should have been the slow unfolding of adolescence became a sprint towards safety, adulthood forced before its time. This is what it means to come of age in Sudan today.

Sudan is young — not in its years, but in the age of its people. Sixty per cent of the population is under thirty, half of them female. Millions of girls have spent most, if not all, of their lives under instability and uncertainty. The consequence of living in survival mode for years is a maturity you never got to grow into but were forced to assume. Childhood and adolescence are compressed, leaving little room for self-discovery or the luxury of simply becoming yourself. Intimate transitions, like starting your period, become reminders of growing up in a time that leaves no room for innocence.

One day you look in the mirror and do not recognise yourself. Just yesterday, you were unaware and uninterested in your body’s changes. Today, you need a bra, your thighs rub together; your reflection feels unfamiliar. Aunties’ comments float by, trivial against the backdrop of war, yet they linger. The ease of adolescence, the relief of not caring, has been stolen.

Privacy is not indulgence. It is where growth happens. It is the space to notice yourself, to understand your own becoming, to exist in solitude. But in Sudan, and even in exile, girls rarely have this space. Everyday life is framed by danger, and even safety abroad feels conditional. For those still in Sudan, fear is immediate; the news of violence and assault shapes how they relate to their bodies before they can understand them. For those who fled, the body remembers what the mind tries to forget, branded by uncertainty about if and when it will ever end.

Survival accelerates maturity, but it never allows you to grow into it. Imagine being twelve when the uprising began, fourteen when Covid shut down the world, seventeen when war forced you to flee the only home you had ever known. Now, at nineteen, you speak like a grown woman, yet are unsure when — or if — you truly became one. You feel old and small at the same time, trying to make sense of feeling sad, grateful, guilty, and scared all at once.

“Stolen girlhood” is not just lost time. It is lost memories, curiosity, ease, and safety. For many Sudanese girls, adolescence never unfolded gently. Each chapter ended before it began, leaving them suspended in a world that demands resilience without reward. They grow up fast, but unevenly — mature enough to care for younger siblings or comfort a mother, yet unpractised in processing their own fear or grief.

By their twenties, young Sudanese women live in limbo. Too burdened to start a future, too jaded to dream. They have spent years waiting for peace, for return, for normality. I am reminded of James Baldwin’s words: “I never have been in despair about the world. I’ve been enraged by it. I can’t afford despair… You can’t tell the children there’s no hope.” But now that those children are grown, what do we tell them?

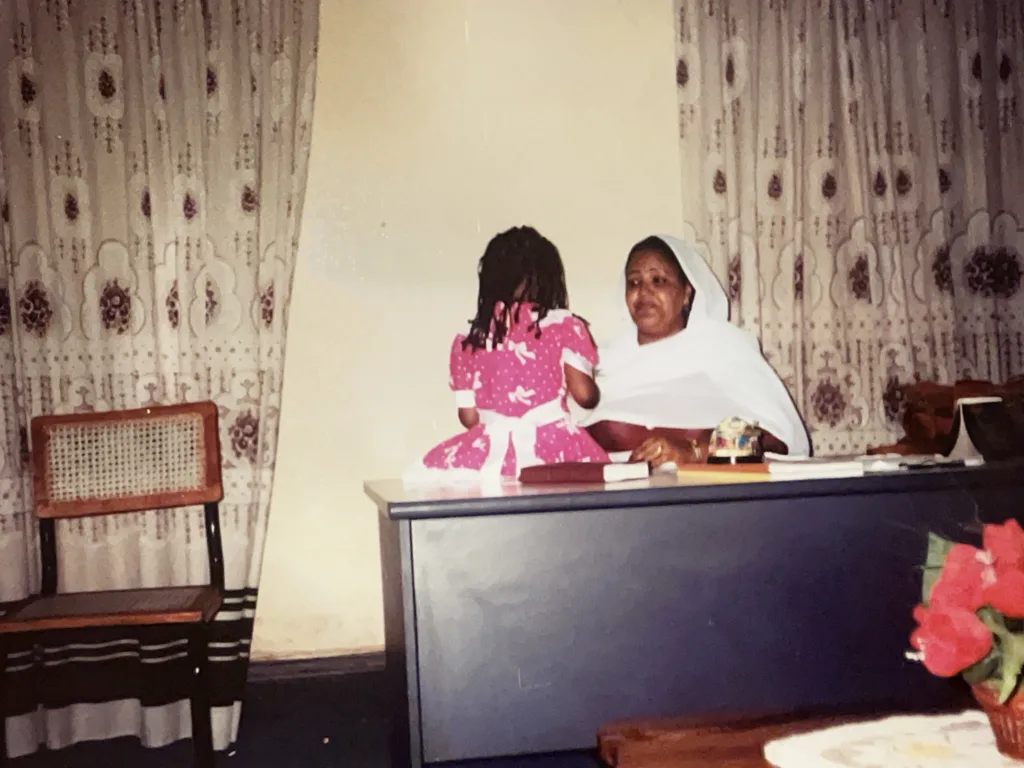

Older generations of Sudanese women carry and share memories of a Sudan alive with ordinary certainty. Mothers persist in repeating inshaAllah kheir, holding families together as if stability could be willed back into existence. All this despite what they have lost: loved ones, life savings in gold, fine dishes that meant nothing to anyone but them, their health, their safety and in a way, their girlhood too. My mother, like many Sudanese mothers, loathes hopelessness. She forbids it. When we speak as if Sudan’s future has already been lost, she reminds us of the Sudan of her childhood — the safety, the laughter, the sense of community she still prays to see again.

Sudanese girls and women are not born stronger than anyone else. Their resilience is not a gift; it is a condition of survival. They deserve quiet mornings and the simple act of moving through life without constant vigilance. They deserve softness, safety, and the ordinary life that was promised to them — the life that war stole.